A friend of mine who does some work I shouldn’t talk about–DC living for you–once explained something that struck me as odd. If you have two unclassified documents, document A and document B. Staple document A and B together–now you may have a classified document. Just the juxtaposition of two pieces of information is information, enough to change the status of the documents.

This was so striking, in fact, I dwelled on it for a bit, and began to realize, that is literally what I do as a computational linguist–re-arrange strings in meaningful ways.

Once you start thinking about this, it appears in a lot of things, aside from the arrangement of textual information. Geographic location is just this in action: real estate is valued by what real estate is next to it; if I own a car on a different continent, that car is essentially worthless unless I’m on that continent; I’m the Emperor of the Moon of the Wholly Circumferential Lunar Empire, yet they refuse to give me a diplomat plate.

Why should information feel so different? After all, re-arranging information is fundamentally what you learn to do in school, and I’ve been in school for 21 years.

I suppose it’s just that. Especially having studied physics, one learns to boil any problem down to its principle components, down to the key relationships that apply, and to demonstrate with those relationships how the facts have come to be. You become a master at re-arranging information in the right way, and when you become a master at re-arranging information, re-arranging information feels cheap; knowing the principle components is the key to finding the solution.

I suppose this is why the juxtaposition of two documents as something meaningful is so striking–if you have access to the two documents before, you have access to the principle components. As a master of re-arrangement, nothing else is required.

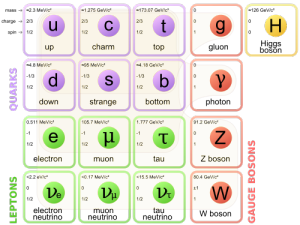

This couldn’t be further from the truth, though. The arrangement of things does matter, and it’s often incredibly complex. If the fundamental components were all that mattered, then if you memorized this chart of the fundamental particles of matter, you would know everything there is to know about everything.

But knowing this chart, you don’t know everything about everything. Their combinations allow a certain freedom, and how those uncertainties left by that freedom are realized are also interesting.

Those uncertainties are just arrangements, but they’re important. They explain how cats are different from birds, why cruising in the passing lane makes you a complete asshole, and why I keep writing this essay despite having far more pressing shit on my plate. All of these things, in many ways individually, are due to arrangements of arrangements of arrangements of fundamental particles, so far removed that the black box of the atomic nucleus bears little (obvious) bearing on the outcome of their combination, aside from making it possible amongst another infinitude of possibilities.

This line of thinking is common outside of physics. For example, after recent events at UVa, some have argued in favor of shutting down fraternities, indefinitely. Counter-arguments in the comments, however, went along the lines of “well, if you kick them out of the frats, they’re still rapists.” They’re treating the members of the organizations as fundamental, principle components, and are arguing that by dividing the principle components up, you do nothing to negate the evil contained in those components.

There’s a lot of places this could go, but I’ve made my point here, loosely enough. Arrangement is information, and it matters. Fundamental components are good to know–they give space for juxtaposition to happen–but the interesting stuff happens in how things are arranged. It’s why we’re more than quarks.